WelCom March 2021

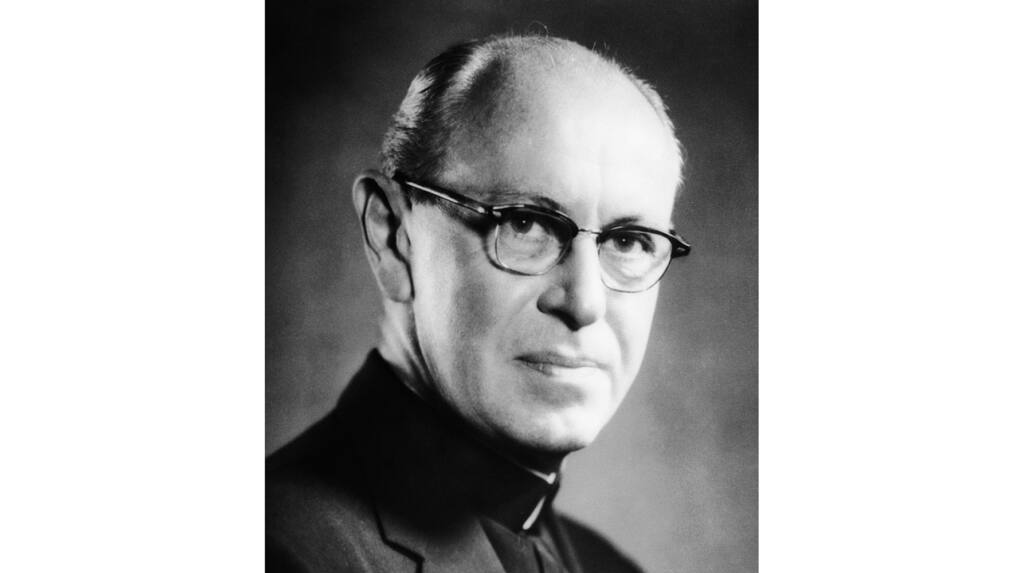

John Courtney Murray SJ, 1904–1967, was an American Jesuit priest and theologian who had a major influence on the teachings of the Second Vatican Council.

He was the primary architect of Dignitatis Humanae, the Vatican II Declaration on Religious Freedom.

Dignitatis Humanae proclaimed religious freedom is the right of every human person, because it is grounded in the dignity of the human person. Above all, it declared that ‘religious freedom is rooted in divine revelation, and for this reason, Christians are bound to respect it all the more conscientiously’.

In Fratelli Tutti, Pope Frances echoes these themes when he speaks about religion and fraternity, and the possibility for a journey of peace among religions when religious freedom is guaranteed as a fundamental human right for all believers (see Par 279).

Mary Eastham looks at the journey of peace among religions which is at the heart of the teaching of both John Courtenay Murray and Pope Francis.

After a year of unprecedented social crisis, no one could deny that public argument in the USA had reached an all-time low. The ravages of Covid-19, the brutal killing of George Floyd, the storming of the US Capitol by armed insurrectionists – all these crises were exacerbated by the constant accusation of ‘fake news’, sorting out the truth from ‘alternative facts’, misinformation and disinformation. This state of affairs brought to mind the prophetic words of John Courtney Murray that: ‘the barbarian is at the gates of the city’.”

When Murray decried the emergence of the ‘barbarian’, a veneer of civility still existed in public life, so that certain language and behaviours would have been considered inconceivable. But what he clearly saw in the 1950s and 1960s was the emergence of the power-broker whose hegemony in the 21st century underpins all the antisocial behaviours listed above. This power broker was the ‘manager’ who viewed all human issues as technical problems to be solved by a morality of means, that is, cost analysis, rather than a morality of truly human ends. According to the great tradition of freedom, the moral ends of a just and fair society were public peace, public morality, social harmony and social justice – and in that order, because each builds on the other.

Between 1955 until his death in 1967, Murray called all people of good will to engage in a great Conspiracy of Cooperation. He chose the word ‘conspiracy’ because its Latin roots, ‘conspiratio’ described the important work to be done. This was a ‘breathing together’, a ‘thinking together’, and a ‘living together’ in order to establish a community of understanding, so that whenever a ‘structure of war’ governed public argument, it could be replaced by principled public discourse.

This is precisely what Pope Frances is asking of us in both the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together, and Fratelli Tutti.

The Document on Human Fraternity is the result of a breathing together between Pope Francis and the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar (Cairo), Ahmad Al-Tayyeb. It is about mutual understanding leading to peace and raises those important social themes which, 20 months later, would be developed in Pope Francis’ Encyclical, Fratelli Tutti.

For example, chapter Six on ‘Dialogue and friendship in society’, speaks of life as the ‘art of encounter’ with everyone… because ‘each of us can learn something from others. No one is useless and no one is expendable’ (see Par 215). Then, most significantly, the Pope referred to the miracle of ‘kindness’, an attitude to be recovered because it is a star ‘shining in the midst of darkness’ and ‘frees us from the cruelty …the anxiety…the frantic flurry of activity’ that prevail in the contemporary era (see Par 222–224).

Kindness… Murray never mentioned the word ‘kindness’ in his public theology, even though I’m sure he believed that respectful public argument could only occur if partners in dialogue were kind to one another. Since Murray loved etymologies, I thought it worthwhile to research the roots of the word ‘kindness’. It is c. 1300, ‘courtesy, noble deeds’, from kind (adj.) + -ness. Meanings ‘kind deeds; kind feelings; quality or habit of being kind’ are from late 14c. Old English kyndnes meant ‘nation’, also ‘produce, an increase’.

Note: the 14c Old English ‘kyndes’ which meant ‘nation’. Is it possible that a nation can be built only when people and groups are kind to one another?

Perhaps only by encountering kindness can the ‘barbarian’ in the United States [and elsewhere] be converted to principled public discourse. It’s worth a try.

Mary Eastham wrote a doctoral dissertation on The Public Role of Religion in Modern Society: A Comparative Analysis of John Courtney Murray and Gustavo Gutierrez for the Catholic University of the America in Washington, DC. She is currently a member of the New Zealand Catholic Bishops’ Committee for Interfaith Relations and has chaired the planning committee of the Palmerston North Interfaith Group since 2011.