‘I am bound, as a pastor, by divine command to give my life for those whom I love and that is all Salvadoreans, even those who are going to kill me.’

‘I am bound, as a pastor, by divine command to give my life for those whom I love and that is all Salvadoreans, even those who are going to kill me.’

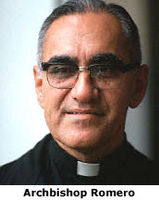

These words appeared in a newspaper just two weeks before Archbishop Romero was shot while celebrating Holy Communion in the hospital which had been his home since 1977.

Quiet, unassuming, conservative in temperament and regarded by the church as safely orthodox, he was an unlikely martyr for the cause of liberation.

Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Goldamez was born in 1917 in Cindad Barrios in the Salvadoran mountains near the border with Honduras. At 12 he began a carpentry apprenticeship, showing promise as a craftsman, but soon thought about ordination. He trained at San Miguel and San Salvador, before completing his theological studies in Rome. Because of the war in Europe there was no member of his family at his ordination in 1942.

Returning to San Salvador in 1944, he served as a country priest before taking charge of two seminaries. In 1966 he started a 23-year tenure as secretary to the El Salvador Bishop’s Conference. He earned a reputation as an energetic administrator and five radio stations broadcast his inspirational sermons across the city of San Miguel.

Romero became bishop in 1970, serving first as assistant to the aged Archbishop of San Salvador and from 1974 as Bishop of Santiago de Maria. Within three years he was Archbishop of San Salvador.

At that time there was growing unrest in the country as many became more aware of the great social injustices of the peasant economy. Nearly 40 percent of the land was owned by a tiny percentage of the population – ‘a nucleus of families who don’t care about the people… To maintain and increase their margin of profit they repress the people’. The majority of ordinary people led impoverished and insecure lives.

Groups of Christians formed to engage in study, worship and group discussion, aiming to follow the gospels and their implications for society. These ‘Basic Communities’ each had their own priest and a leader elected from among the group.

The landowners were alarmed at the sight of uneducated peasants choosing their own spokespeople and concerning themselves with social issues in the name of Christianity.

Virulent press campaigns were conducted against them, with accusations of Marxism. Right-wing gangs emerged to carry out active persecution and killings. Men and women vanished without trace or reason. Death squads roamed the countryside and soldiers attacked any protesters in the square of the capital.

Romero protested at the killing of men and women who had ‘Taken to the streets in orderly fashion to petition for justice and liberty’. There were, of course, those who sought change through violence, seizing land and giving landowners cause to react, but Oscar Romero condemned all forms of what he called ‘the mysticism of violence’.

The politics of the common good

One priest, Fr Rutilio Grande, was particularly outspoken in denouncing the injustices against the 30,000 peasants working 35 sugar-cane farms in his area. Archbishop Romero defended Fr Grande against official criticism: ‘The government should not consider a priest who takes a stand for social justice, as a politician, or a subversive element, when he is fulfilling his mission in the politics of the common good’.

In March 1977, Fr Grande and two companions were murdered.

Archbishop Romero was summoned to view the bodies – a hint of what happens to meddlesome priests. This and the lack of any official enquiry convinced him that the government employed – or at least supported – people who killed for political convenience. He responded by prohibiting the celebration of Mass anywhere in the country on the following Sunday except at his own Cathedral, a celebration to which all the faithful were invited – and came – overflowing in their thousands into the plaza outside.

The event served to unite the faithful and remove any doubts about Romero’s commitment to justice. The government, of course, was furious, even more so as the church began to document civil rights abuses and seek the truth in a country governed by lies. Visiting the Pope in 1979, Archbishop Romero presented him with seven dossiers filled with reports and documents describing injustices in El Salvador. Less than a year later he was killed.

In the sermon just minutes before his death, Archbishop Romero reminded his congregation of the parable of the wheat. ‘Those who surrender to the service of the poor through love of Christ, will live like the grain of wheat that dies. It only apparently dies. If it were not to die, it would remain a solitary grain. The harvest comes because of the grain that dies… We know that every effort to improve society, above all when society is so full of injustice and sin, is an effort that God blesses; that God wants; that God demands of us’.

He gladly accepted what he knew would happen.

http://www.justpeace.org/romero.htm