NauMai September 2021

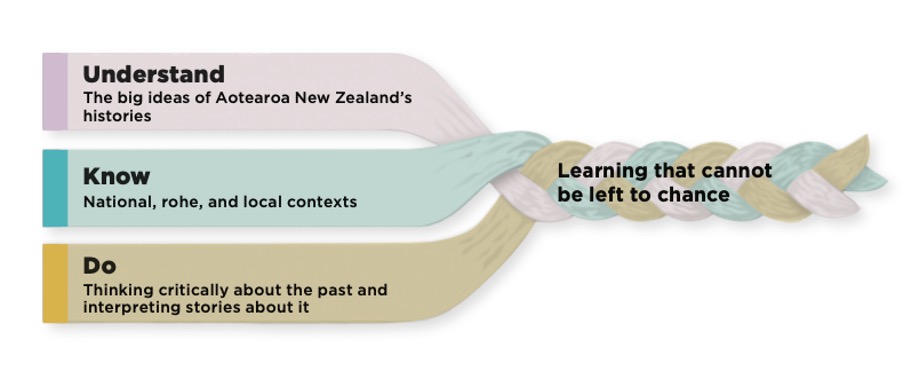

Following campaigning led by students of Ōtorohanga College, from the Waikato region, two years ago the government announced that history of Aotearoa New Zealand would be required in the school curriculum to year 10. The proposed history curriculum encourages learners to be critical citizens – learning about the past to understand the present and prepare for the future. There are three elements to the curriculum content: UNDERSTAND, KNOW, and DO. From 2022, Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories will be taught in all schools and kura.

Lisa Beech and Jim McAloon provide comment through the lens of Catholic social teaching.

Remembering is an essential part of our Christian lives. In our gatherings we consciously remind ourselves of thousands of years of faith. We listen to ancient texts recalling the historic relationship built between God and people through the covenant with Abraham and his descendants. We join in precious traditions and rituals passed on by countless generations. We relive the life and death of Jesus Christ, and memorialise details of his mission and the lives of his followers in feast days, passing his message on to future generations.

But remembering has other dimensions. Pope Francis has said we have a responsibility to remember historic wars, events such as the Shoah (Holocaust), and the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

‘We cannot allow present and future generations to lose the memory of what happened…. Nowadays it is easy to be tempted to turn the page, to say that all these things happened long ago and we should look to the future. For God’s sake, no! We can never look forward without remembering the past; we do not progress without an honest and unclouded memory.’ – Fratelli Tutti paras 248-249

Following the 2018 Synod on Young People, Pope Francis spoke of the importance of history in developing young people’s critical and cultural awareness (Christus Vivit paragraph 181). Two years ago, on 12 September 2019, the New Zealand government announced that history of Aotearoa would be required in the school curriculum to year 10. The decision followed months of campaigning by teachers and students – including a 13,000-strong petition for a day to commemorate the New Zealand Wars, launched by students at Ōtorohanga College.

Catholics and the wider community have been considering Ministry of Education proposals on implementing the government’s decision.

The Wellington Archdiocese Ecology Justice and Peace Commission’s submission to the Ministry recognises the importance of including the history of Aotearoa New Zealand in the curriculum.

As the New Zealand Catholic Bishops’ Conference said in their 1995 statement on the Treaty of Waitangi: ‘We all need to know our history and the different legacies it has left to Māori and Tau Iwi… We have an opportunity to heal wounds that have been present for too long.’

More recently, the 2017 Synod outcomes for the Archdiocese of Wellington included several recommendations about our history:

- ‘The Archdiocese is a voice seeking “tika me pono” (truth and justice) to right wrongs in the history of Aotearoa.

- The Archdiocese captures the shared story of our history.

- The Archdiocese continues to provide education about our history, including challenging racism in attitude and practice.’

These recommendations are both necessary for us as a church community, and worthwhile for wider society. It is especially important for tamariki Māori – Māori children – to see themselves in the stories of the past, and for all young people to understand historic rights and wrongs that have occurred here.

The consequences of colonisation continue to be experienced by Māori and all New Zealanders need to gain a greater understanding of this. It is also to be hoped the new curriculum will reflect the stories of the many peoples who have made Aotearoa New Zealand their home.

Healing our history can be challenging for those of us brought up more on European histories of kings and queens rather than on accounts of the people of the Pacific. And some may suggest that history is a dead past.

However, all communities choose what they will remember, [for example] many thousands of people choose certain remembrances around Anzac Day. History reaches into the present, as we were all reminded by the moving events that accompanied the government’s recent apology for the mid-1970s dawn raids, which targeted Pasifika peoples. During and following the apology, many Pasifika leaders have spoken of the enduring hurt those raids caused. If reconciliation follows the apology, that reconciliation will also be part of

the history.

As Pope Francis reminds us, history does not only consist of injustices but also of acts of goodness, which provide examples of reconciliation and peace-making in difficult circumstances. ‘To remember goodness is also a healthy thing,’ he says (Fratelli Tutti, #249). More generally, an understanding of history is essential to a society in which all are informed and able to participate in political, social, and cultural affairs.

Lisa Beech is Ecology, Justice and Peace Advisor in the Archdiocese of Wellington. Jim McAloon is Chair of the Wellington Archdiocesan Commission for Ecology, Justice and Peace, and is a Professor of History at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington.

Catholic education leaders comment

Dr Kevin Shore, CEO, New Zealand Catholic Education Office

“The new history curriculum is asking us to reflect on our place and our part in this place. It can be tough for people to get their heads around the negative aspects of our history but there are many positive aspects as well. Telling the interesting aspects of our local history is very important if we are to fully understand the place we stand on.

The new curriculum provides a great deal of choice on what you can choose from in terms of context for teaching New Zealand history. From a Catholic perspective there is a lot to be told and to contribute from our history – including some of the things that weren’t so great. There is a lot of scope within this new curriculum to tell our stories with integrity.

It is a positive space for the Catholic Church – the history of Catholic education and its part in the development of our society is strong in terms of contributing to equity, justice and dignity. From our first Catholic missionaries and some of our first schools we have almost 200 years of Catholic education in this country. For example, the early missionaries led by Bishop Pompallier in Northland and his involvement in the signing of the Te Tiriti and Suzanne Aubert’s missionary work supporting local Māori on the Whanganui Awa and elsewhere.

There are many untapped stories about our faith path in Aotearoa involving Māori and Pākehā working together as well as some of the challenging aspects. The new curriculum provides a good place for us to learn and to be fully informed about our own history in this country.”

Colin MacLeod, Director, NCRS – National Centre for Religious Studies, Te Kupenga

“It’s wonderful that rich histories of Aotearoa will form part of the New Zealand National Curriculum, especially inclusion of powerful stories of Māori, which need to be heard and celebrated or mourned. We at NCRS certainly anticipate this move complementing aspects of the emerging new Religious Education Curriculum for Catholic schools. It’s just so important for tamariki in our schools that they know their stories and where they have come from, and especially in our context, who we are together as disciples of Jesus.”

Colin MacLeod is also chair, NZCBCIR – New Zealand Catholic Bishops’ Committee for Interfaith Relations; and chair, RSTAANZ – Religious Studies Teachers Association of Aotearoa New Zealand.

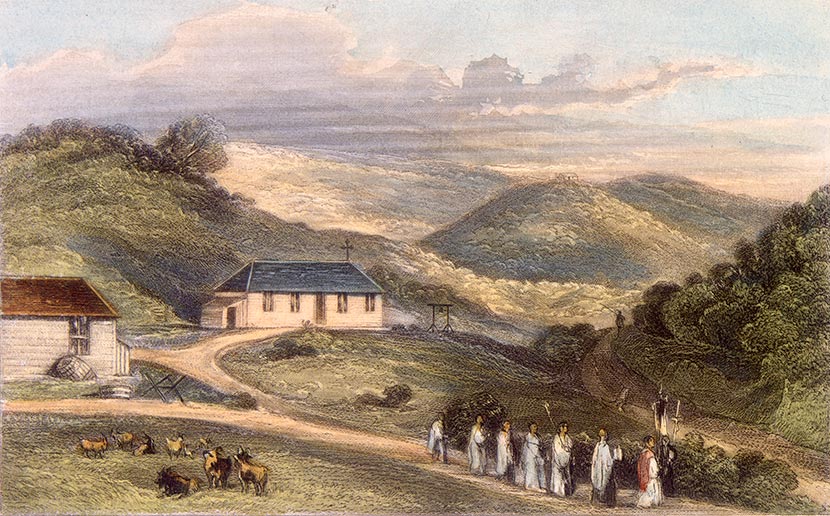

This hand-coloured engraving 1847, after a drawing by Samuel Brees, shows a religious procession outside the first Catholic chapel in Port Nicholson – Wellington. It was opened in 1843 and headed by Fr Jeremiah Purcell O’Reily, an Irishman who had arrived that year with the New Zealand Company, as Wellington’s first Catholic parish priest. Built on what became Boulcott Street, this chapel was replaced in 1874 by the church of St Mary of the Angels. The church was destroyed by fire in 1918 and the present St Mary of the Angels opened on the same site in 1922.

When Fr O’Reily first arrived, he lodged with Mrs Kennedy in Cuba Street. He estimated there were about 200 Catholics in Wellington, including many Māori, attending Sunday Mass in the chapel. As the only priest for hundreds of miles, Fr O’Reily’s pastoral care took him as far afield as Taupō and south to Nelson. This responsibility was shared with the Marists when they arrived in Ōtaki the following year, 1844, to work among the Māori people.