WelCom December 2023

The Wellington Abrahamic Council hosted a public seminar last month on the ever-increasing impact of technology on religions and how to adapt in the post-AI age.

Questions included: What are our religions’ positions on technology in general, and AI specifically? How could AI impact our religious beliefs and practices? Can a machine be conscious or have a soul? How do we mitigate potential threats AI poses to humanity, to religion and to God?

Keynote speakers offering perspectives from the three Abrahamic religions included Dave Moskovitz (Jewish) – Jewish Co-chair of the Wellington Abrahamic Council and a software developer also involved in AI initiatives in education; Harisu Abdullahi Shehu (Muslim) – a data scientist with MSD and an adjunct AI researcher with VUW; and Petrus Simons (Christian) – a Lutheran member of the Roman Catholic-Lutheran Dialogue Commission, whose PhD thesis is on the impact of technicism and economism on agriculture.

An abridged version of Petrus Simons’ presentation is below.

A Christian perspective on Artificial Intelligence

Petrus Simons

The release at the end of 2022 of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, where GPT means a generative pre-trained transformer for a Large Language Model (LLM) caused quite a stir. The power of these models to produce a wide range of texts from databases, which are hardly indistinguishable from originals, raised many questions. As they learn very fast, their increasing power, it seemed, might be used for evil as well as for good purposes. What if we became completely dependent on them?

Geoffrey Hinton, known as the godfather of AI, was one of those sounding alarm. He feared that humanity faced an immediate threat of a super-power AI. As he put it: ‘My intuition is: we are toast. This is the actual end of history. We may end humanity in twenty years.’

Already in 1972, he believed that human thought was not just logic, but rather linguistic, represented by words. As a thought is: ‘just a great big vector of neural activity’, he believed that a model of the human brain and its neural networks would be able to reproduce human language. An algorithm (a step-by-step procedure) should be able to learn by adjusting the connecting strengths between artificial neurons in response to new data.

In 1986 Hinton had helped develop algorithms that could reweight the connections in a neural net, so that a machine could in theory begin to learn on its own. AI would catch up with the brain eventually. Recently, he said: ‘I didn’t think it would overtake it that quickly’.

Hinton’s pessimism is not shared by all his colleagues, although they have concerns too. Michael Luck, for instance, mentioned last April that existing AI systems trained on datasets full of unexamined biases, are shaping major decisions that companies take, ranging from job applications to the approval of loans.

In general, the new models come at the end of almost a century of attempts to computerise data processing ranging from making fast calculations, problem solving to Internet, digitisation, and cell phones.

‘The Enlightenment of the 18th century appreciated sciences as potential sources of technical innovations to achieve progress. The new science of economics became part of this.’

We should see this within the perspective of the Industrial Revolution, which took off around 1785 with James Watt’s perfection of Newcomen’s steam engine, amongst other things by equipping it with an automatic speed-regulating device.

This has initiated a process of constructing a ‘sixth continent’ of mechanical and automatic systems of transport, production, distribution and administration. This artificial system requires huge volumes of raw materials and energy, which must be supplied by the five real continents. Pollution, global warming and declining biodiversity are the prices we pay.

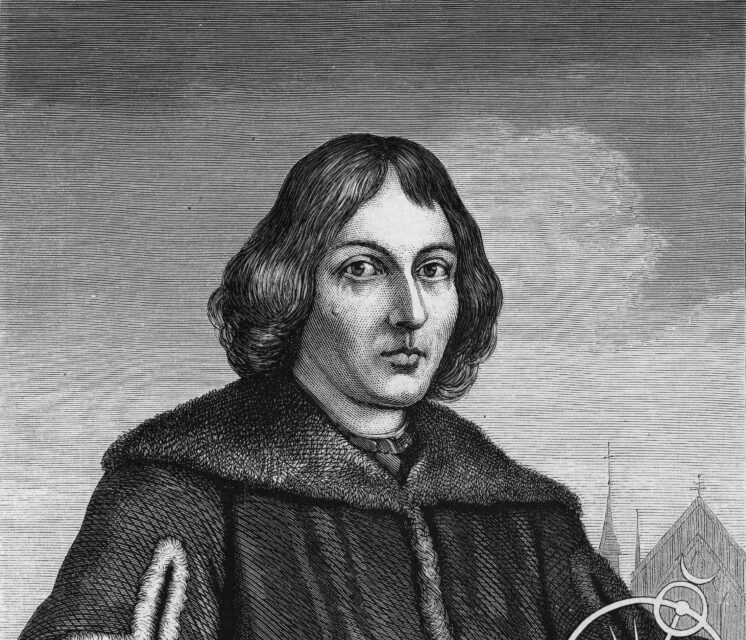

The mechanisation of Western civilisation began during the Renaissance of the 16th century, with Copernicus’ discovery that the earth orbits the sun. This was seen as a mechanical process, which can be described in mathematical equations.

The philosopher and mathematician René Descartes (1596–1650) has been a key figure with an enduring influence on the mechanisation of the world. I quote:

Knowing the force and action of fire, water, air, the stars, the heavens, and all the other bodies that surround us, as distinctly as we know the various crafts of our artisans, we might also apply them in the same way to all the uses to which they are adapted, and thus, render ourselves the lords and possessors of nature. And this is a result to be desired, not only in order to invent an infinity of arts, by which we might be enabled to enjoy without any trouble the fruits of the earth, and all its comforts, but also and especially for the preservation of health…

Descartes believed that the human body, including the brain, as well as plants and animals are all physical mechanisms, robots, or automata. As humans we stand apart because God has lodged an immortal rational soul into our body.

Thinking, Descartes believed, should be done methodically, using four steps:

- Exclude all grounds for doubt.

- Divide difficulties into as many parts as possible.

- Commence with the simplest and easiest elements and ascend step by step to the knowledge of the more complex.

- Make enumerations as complete as possible (Discourse Part II, p.15, abridged).

We would call this method an algorithm. He saw it as a means of rationally re-constructing reality.

The Enlightenment of the 18th century appreciated sciences as potential sources of technical innovations to achieve progress. The new science of economics became part of this. The price mechanism should direct the pattern of production and consumption to maximise profits. To keep ahead of the competition producers should apply technical innovations as soon as possible, regardless of any problems that might ensue. This is what Egbert Schuurman [Dutch engineer, philosopher, politician, and Emeritus Professor of Philosophy in the Netherlands] calls technicism, a huge over-estimation of science and technology.

‘As humans we stand apart because God has lodged an immortal rational soul into our body.’

Every sphere of life is being drawn into this mechanical, automatic, universe. Today’s LLMs are now technicising language, scripture, literature, communication, words in short.

The way of Descartes has not been the only way, although we, including Christians, have made it our own. Another, more principled biblical way was shown by Blaise Pascal (1623–1662), but not followed. He too was a very gifted scientist and philosopher. After his death a piece of paper was found in his coat on which he had recorded a vision, beginning with these words:

- FIRE

- God of Abraham, God of Issac, God of Jacob.

- Not of philosophers and scholars.

- Assurance. Assurance. Sentiment. Joy, Peace.

- God of Jesus Christ.

Whereas philosophers have been thinking of humans as subjects who see the world as objects, with the gap to be bridged by reason. Pascal found certainty, assurance and peace in the God of Abraham and his sons, the God who revealed Himself to human beings in His word, in his creation and in His own Son, through whom He created the world as a wonderful cosmos. This God is the Sovereign Ruler, who has subjected the whole cosmos to His laws.

He led his people out of Egypt. He assured Moses (Exodus 3) that His name is I Am, the one you can trust, In the fullness of time he sent His Son, the Messiah, who died for the sins of the whole world.

We have been created in the image of God, as living souls, to reflect Him in all we are doing, from our heart, by faith. There is no gap between us and the creation.

Instead, we have chosen to reflect idols.

The first Adam had to be removed from paradise, the garden entrusted to his care and protection, because he exalted himself to be God. Jesus Christ our Lord, the second Adam, humbled himself even to death on a cross, but is now seated at the right hand of the Father. He will make sure that history continues such that in the kingdom of God there will be a city-garden. The signs of this communal garden can be observed here and now.

Chatbots will not terminate humankind. We are not toast, but our modern technicistic civilisation might well become toast. It is already crisis prone.

We may trust the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob to show us a new way, a way of loving people, and all creation, even by means of technology. He will help us promote a responsible ethics for AI.