WelCom October 2023

Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ,

I have a little litmus test when I meet someone who wishes to discuss the Catholic Church. I tend to start off by saying something like, ‘I believe the Roman Catholic Church, has been, is now, and will continue to be a tremendous force for good in the world.’ I then look and listen carefully for their response. My experience too often is that even those who profess a strong Catholic faith baulk at this statement – it appears to be too bold a statement.

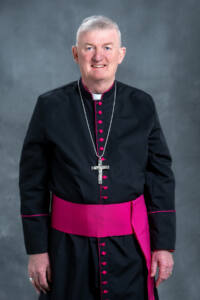

I welcome this opportunity to contribute on a regular basis to this Catholic news publication, and my aim is to, over time, defend my love for the Church. I have given my whole life to her, I love her very much, and as you know have recently been ordained as one of her bishops. The following formed the basis of my recent first homily in the Cathedral of the Holy Spirit in Palmerston North. It has been based on a recent article from the US magazine First Things by John Duggan [free-lance writer, based in Surrey, England].

In the great capital city of Ireland, Dublin, all is not well. Almost unbelievably there has been a recent travel advisory from the American Government warning its citizens about Dublin. It gave the advice that American citizens should avoid going out at night or walking through the city alone. The advisory comes as a result of recent instances of tourists being violently attacked and, in some cases, suffering life threatening injuries. These attacks are in fact part of a wider trend – all over Ireland rates of assault by groups of young people are on the increase.

Dubliners are shocked by this and lament the decline of their international image as a people of an easy and gentle demeanour. In the Irish media, the tone surrounding this discussion shifts between the uncompromising ‘Failure to address crime is handing control of our streets to thugs and louts’ to the personal ‘I am proud to be an Irish citizen, but Dublin is an embarrassment’ and the more cerebral ‘O’Connell Street represents a spectacular failure of what our Republic should be’. Residents of the housing complex near the most recent assault are reportedly afraid to come out of their apartments at night.

The political response has been predictable. At the top, government leaders are walking the line between acknowledging that something may be very wrong while, understandably, stressing the need for perspective. Lower down the chain at local-body level the response has been more bullish: The Lord Mayor of Dublin is reportedly developing plans for ‘a city of kindness’. The debate as a whole seems to be oscillating between, on the one hand, appeals for greater police presence on the streets and harsher enforcement of the law; and, on the other, calls for more investment in drug-treatment programmes and diversionary activities for young people.

Our natural desire for the good, whilst written on every human heart, requires us to also regularly make an act of our will to bring our search for the good, into the light.

This is not an attempt by me as a new bishop to score easy points by moralising, for surely the Church is at her worst here, but I do want to propose to you that this malaise has its roots at a deeper level than any of the aforementioned commentators have mentioned. In the end I think we are able to say these problems, in Dublin, or indeed here in New Zealand, are not likely to be remedied by political slogans or external fixes. No, something else is going on here – and it’s at an interior level. You see, in the end, people are governed by a firm, inherited sense of right and wrong. And if that’s the case, there is a question: where does a person find their moral compass, and better still, have this nourished?

Back to Dublin where various social commentators are voicing their views. Irish poet Theo Dorgan noted that the presence of the Catholic Church in Irish institutions and social mores was now ‘smoke in a gale, dust in the wind’. However, there was a danger that with Catholicism would go ‘the foundational ideals of justice, charity, compassion and mercy. We can already see the damage done in our country’s short-lived flirtation…’ with post-Christian society he comments. The people of Ireland, Dorgan concludes, ‘would do well to begin thinking clearly, and very soon, about what we will choose for the moral foundations of a post-Catholic Ireland.’

Sally Rooney the 32-year-old bright star of the Irish literary scene wrote recently, ‘It seems to me that…free-market ideology has replaced Catholic ideology…but what has replaced the values we had on community, family and things like that? The free market has nothing to say about, no concern for, and in fact has even open hostility towards these things. To me, it doesn’t seem like straightforward progress. We got rid of the Catholic Church and replaced it with predatory capitalism…’.

I’m sure every Catholic person is aware the Catholic Church has far more to offer than simply a role as a moral policeman. No, once again, we are concerned with the issue of personal conversion and our interior disposition, a disposition that naturally orientates us towards the good. The Church teaches us further that there are goods beyond our individual appetites and these are articulated for us by the Church. Our natural desire for the good, whilst written on every human heart, requires us to also regularly make an act of our will to bring our search for the good, into the light. Failing to do this we run the risk of this desire becoming permanently buried, as evidenced by the perpetrators of wanton violence.

I want to finish with the insight of a German man called Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde. He was a German constitutional theorist, a high-court judge, and a practising Catholic. Back in the sixties, he described a critical paradox at the heart of modern Western democracies: He said this: ‘The liberal, secularised state lives by prerequisites which it cannot guarantee itself. This is the great adventure it has undertaken for freedom’s sake…. As a liberal state it can endure only if the freedom it bestows on its citizens takes some regulation from the (human) interior, both from a moral substance of the individuals, and a certain collective of society at large. On the other hand, it cannot by itself procure these interior forces….’

The liberal Irish state, and surely indeed our own country of New Zealand, may find itself, as Böckenförde would have it, more and more stripped of certain moral prerequisites among the population. Yet the state is at a loss to secure these prerequisites in any reliable way. Liberal states cannot instil moral force among their diverse, autonomous citizens; they must instead, in the words of Pope Benedict XVI, ‘presuppose it and construct upon it.’

Roman Catholicism, as it has done for 2000 years, has a critical role to play in orientating society towards the good. She has this mission because her founder, Jesus, knew that mere proclamation of virtue would never suffice unless it was accompanied by a deep and ongoing conversion to Christ.

+ John Adams