WelCom November 2020

Thinking after Covid-19: guests at the Lord’s table

The pandemic has made anyone who enters a church sensitive like never before to how we are arranged in the building. Two metres apart! No bunching up! Signs on seats where we may sit. Tape on other seats making them off limits. Signs on doors giving the maximum number that may enter – always a lot fewer than the originally intended number. It is all such a hassle; and many sigh for the time when we can get back to normal! But should we? Was the old normal that good? It may be familiar – and that is always comforting in a stressful time – but was it well thought out? Was it ever really fit for the purpose of our liturgical gathering?

Was the old normal fit for purpose?

Look at this picture of the old normal.

It is typical of the vast majority of Catholic church buildings the world over. Seats, set out in row after row, with the intention that those sitting there can see the special area – marked off in various ways – known prior to Vatican II, but still referred to by many, as ‘the sanctuary’.

It is built around the notion that the priest says Mass, and the laity attend Mass – a basic division that was replicated in any number of ways in Catholic liturgy for centuries. The priest was the focus, the congregation just happened to be there. The priest’s part took place in the holy space, the laity in the ordinary space of the church. The cleric prayed in Latin and it was the Church’s official prayer; the laity prayed in various ‘vernaculars’ (a derogatory term equivalent to ‘patois’ which literally means ‘the speech of the servants’) their individual private prayers. The clergy belonged in their special space where they could move and act; the laity could just stand, kneel or sit in a bench. The two parts of the church building – separated by rails – corresponded to the two parts of the Church separated by Holy Orders. Such buildings’ arrangements are an expression in wood and stone of clericalism.

It was this two-tier model of liturgy that Vatican II sought to change by reminding us that the liturgy is the work of the whole community of the baptised. We, all of us whatever our special tasks, celebrate the liturgy because it is the service of God by his whole People. But in the years after Vatican II, few got the message. The altar table was pulled out from the back wall or a small table placed in front, as in this picture; but the two-part building remained, more or less intact – as, indeed, did clericalism.

But surely this is the best way for all to see?

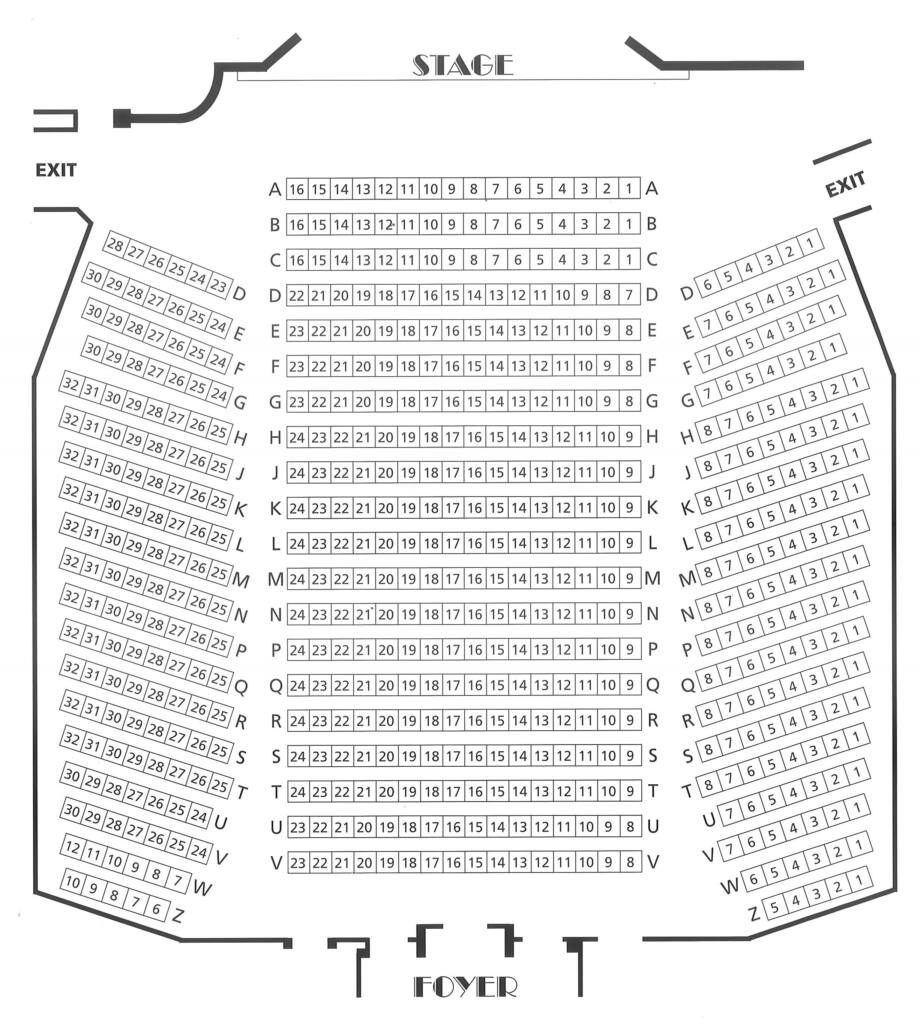

Now look at this diagram:

This is a seating plan for a theatre, but it could be a church because it has the exact same special arrangement. Indeed, now with the pandemic, many churches have adopted just such seating plans to show you where you can, and cannot, sit. This arrangement is perfect if you (along with many other individuals) all want to watch a performance by the actors on stage – but is that what we are when we assemble for the Eucharist?

If I am a member of an audience, then I want to see without interruption and my focus is on the stage, and there is a barrier – what actors call ‘the fourth wall’ – between me, a consumer of the play/film/performance, and the production. But in liturgy I am part of the production, we are all in it together, we are all actors in the Christ as his sisters and brothers in baptism. The very fact that most church buildings have seating arrangements, which exactly parallel theatres, illustrates that the old normal was/is anything but ideal. Just as we are celebrants rather than consumers (refer to https://international.la-croix.com/news/we-are-celebrants-not-consumers/12392) when we assemble liturgically, so we should think of ourselves as actors on the stage rather than audience in the stalls.

Called to his supper

So what should it be like? The starting point is to note that in our liturgy we experience anew being present at the Lord Jesus’ table: he has called us friends (Jn 15:15) and as such we can sit at table with him. This sitting at table anticipates being seated at the heavenly banquet ‘many will come from east and west, and recline at the table with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven’ (Mat 8:11). The table – the banquet – and having a place at the banquet table is, a basic liturgical motif most Catholics simply do not know from their experience (despite hearing references to it at every eucharistic assembly).

Look at any table set out to welcome people. The table forms the centrepiece and the guests sit around it. Watch people in any restaurant. They will face each other across the table, and if more come to sit down they will locate themselves between those already there.

Here we have a basic liturgical shape that is built out of the nature of what we are doing when we assemble, rather than one just picked from a common form – the ancient theatre – and imposed on the Lord’s Supper. This is the eucharistic shape of space, not the familiar shape of most of our current buildings.

Creating a new space

Does it matter? It matters for several reasons. First, if we are to experience anew the promises of Jesus – which is the meaning of ‘remember’ – then we have to have an adequate location for those experiences. A gathering around the table, when remembered, means we gather around a table! Second, during Covid-19 many have asked if ‘going to Mass made much difference?’ This can only be answered by offering a new, renewed, experience: only when I know what I am taking a part in can it really make sense to me. If I feel it is ‘just an event I attend,’ then there is little reason why we should not simply have it as a performance we tune into on a computer. And third, we use the language about sitting at table, gathered to the Supper, and being around the Lord’s table – but if this does not happen, we experience cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance relating to any matter tends to precede rejection of something as being either irrelevant or false.

But perhaps there is an even more pressing reason for moving to a whole new layout of a table and people sitting and standing in a circle around the table. It is part of the battle against the clericalism that is deforming the Catholic Church. We have a look at this picture of the chapel of the Presbyterian College at McGill University in Montreal.

Many western churches have taken on board in recent decades the notion, from Vatican II, that the eucharist is the centre and summit of the Christian life – and we can see this expressed in the way this chapel is arranged. But look also at the fact that each person, a baptised sister or brother, each has the same chair in this assembly. All are around the table, but all are equal in dignity, each has a place, and the Lord’s table is the focal point. The table is the centre and each must respect everyone else as fellow pilgrims. Perhaps we have something to learn from this picture. If we critique clericalism in our ecclesiology, then we must express that critique in our furniture and spatial arrangements. It is mere words to reject clericalism, if the basic experience of our worship – our experience of the space around us – simply reinforces it. We need to experience anew the Lord’s invitation to come and sit at table, not experience anew the clericalism that Pope Francis says we must reject. Changing the furniture would not fix the problem, but the furniture must be changed if we are to fix the problem.

Thomas O’Loughlin is a priest of the Catholic Diocese of Arundel and Brighton, emeritus professor of historical theology at the University of Nottingham (UK) and director of the Centre of Applied Theology, UK.